The project ‘Uncover the secrets of the human body in an anatomical theatre of the 21st century’ which is being carried out in the years 2020–2022.

Co-financed by the programme ‘Social Responsibility of Science’ run by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

The Medical University of Warsaw has received funding of PLN 266,175.51 in response to its application submitted to the programme ‘Social Responsibility of Science’ run by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

The Project is being carried out by the Museum of the History of Medicine, with the assistance of other entities within the university, and is headed by Dr Adam Tyszkiewicz, director of the Museum of the History of Medicine at the Warsaw Medical University.

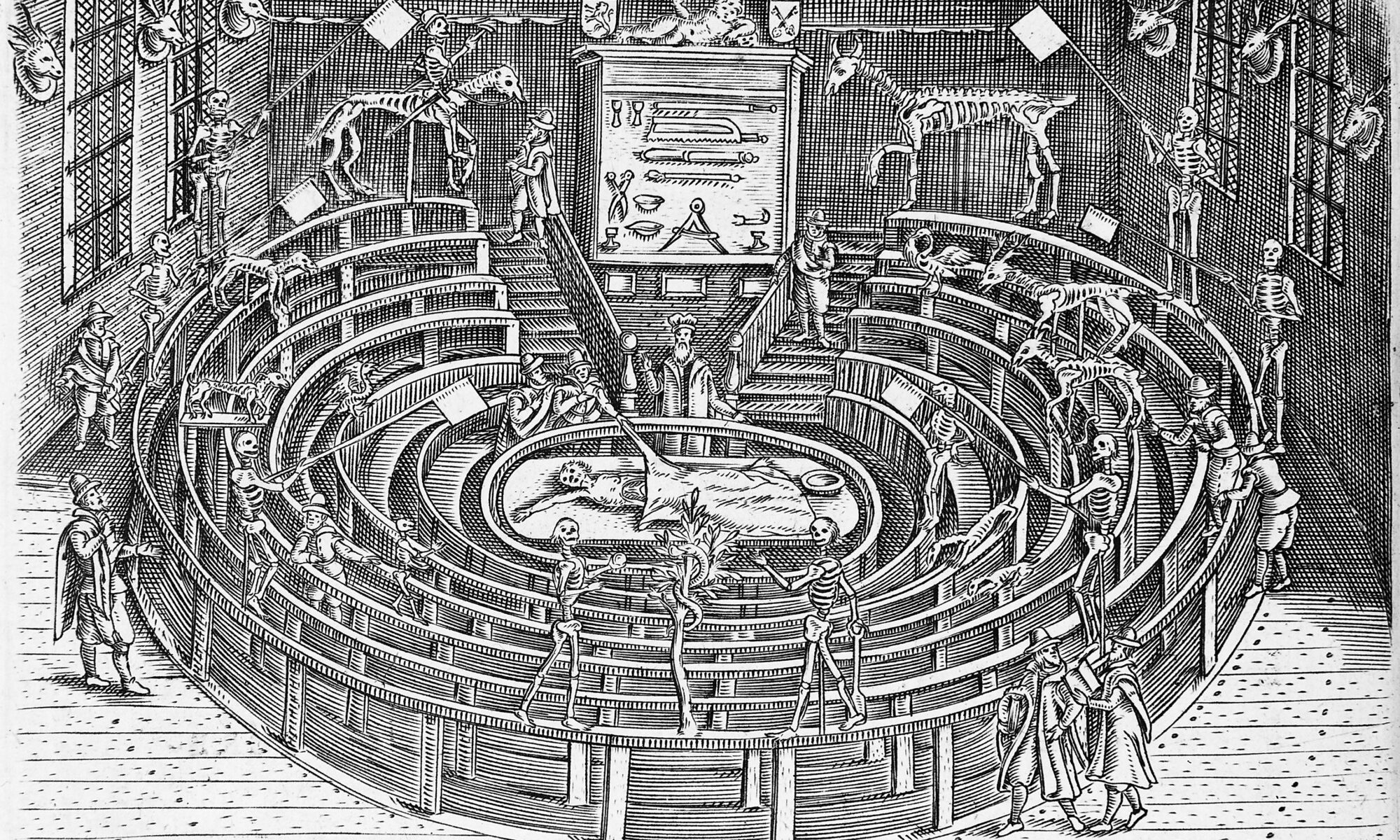

As part of the project, a teaching room will be set up modelled on early modern anatomical theatres, in which classes and practical workshops will be held, as well as scientific meetings to popularize the history of medicine, pharmacy and their relationship with the humanities. In addition, a series of open lectures will be delivered by specialists in the aforementioned fields.

The aim of the Project is to promulgate the current state of knowledge on the human anatomy among young people and adults so as to increase social awareness on the functioning of the human body, provoke an interest in the medical sciences among the participants, and awaken their curiosity through the presentation of knowledge both from the perspective of the medical sciences as well as the humanities. Furthermore, the project has the objective of familiarizing the audience with the profiles of renowned Polish anatomists whose biographies encompass both their scientific activities and their services to their homeland. We are hoping to make available a modern space which will continue to function when the ministerial programme ends.

During a series of classes held in the anatomical theatre, young people from secondary schools and groups of adults from selected organizations – such as associations, retirement homes, universities of the third age – will get to learn about medicine and the humanities. The remaining group of participants, i.e. all other interested parties, will have the opportunity to become acquainted with attractive themed presentations by specialists in various disciplines which are broadly related to human anatomy.

Therefore, we warmly encourage you all to follow our project website where you can find updates about the progress of our activities and planned events, and knowledge for all in the field of anatomy.