Without a doubt, the most controversial anatomical atlas in the history of medicine. Its author was the Austrian anatomist and rector of the University of Vienna Edouard Pernkompf (1888-1955). He invited four artists who were responsible for the preparation of the illustrative material of the Atlas. Initially, in the years 1937-1941, two volumes devoted to the anatomy and muscles of the abdomen, pelvis and pelvic limbs, respectively, were published. The album was famous for its amazingly beautiful, colorful drawings and from a scientific point of view it was a scientific masterpiece. His assessment was overshadowed by the affiliation of Pernkompf and his assistants to the Nazi party, which was revealed in the album itself by the Nazi symbolism emphasized in many places. The use of the bodies of WWII victims and Nazi ideology for dissection was even more controversial. After the end of the war, Pernkopf stayed in an Allied prison for several years, then returned to work on the next volumes of the atlas. In 1952, the third part devoted to the head and neck was published, while the devil appeared after his death. In total, in the second half of the 20th century, the Pernkopf Atlas was published in five language versions.

Without a doubt, the most controversial anatomical atlas in the history of medicine. Its author was the Austrian anatomist and rector of the University of Vienna Edouard Pernkompf (1888-1955). He invited four artists who were responsible for the preparation of the illustrative material of the Atlas. Initially, in the years 1937-1941, two volumes devoted to the anatomy and muscles of the abdomen, pelvis and pelvic limbs, respectively, were published. The album was famous for its amazingly beautiful, colorful drawings and from a scientific point of view it was a scientific masterpiece. His assessment was overshadowed by the affiliation of Pernkompf and his assistants to the Nazi party, which was revealed in the album itself by the Nazi symbolism emphasized in many places. The use of the bodies of WWII victims and Nazi ideology for dissection was even more controversial. After the end of the war, Pernkopf stayed in an Allied prison for several years, then returned to work on the next volumes of the atlas. In 1952, the third part devoted to the head and neck was published, while the devil appeared after his death. In total, in the second half of the 20th century, the Pernkopf Atlas was published in five language versions.

Mondino de Luzzi (Mundinus), Anathomia Mundini, 1316 (printed in 1476)

The first work on anatomy since ancient times based on the results of an autopsy. Its author, Mondino de Luzzi (1270-1320), called the “restorer of anatomy”, received his medical education at the University of Bologna. During Mundinus’ lifetime, performing an autopsy was not the basis of medical training, but this did not prevent him from being the first physician to perform an autopsy since the times of Herophilus and Erastritos in Alexandria in the 3rd century BC. His life’s work “Anathomia”, was not however, an original work, as it was based primarily on knowledge from the times of Galen and on the results of research from the various Arab schools. In several places the author allowed himself, but very carefully, to undermine Galen’s authority, but this did not translate into the whole work. Mundinus’ descriptions were also imprecise, and the illustrations supporting them did not reflect the exact structure of individual organs and their arrangement in the cavities of the human body. This was due to the fact that dissection at that time was more like quartering and had nothing to do with professional preparation of the body. The preparations he prepared for educational purposes were dried, for example, in the sun in order to show the structure of tendons and ligaments. Until the sixteenth century, however, “Anathomy” was the most widely published publication in universities on the structure of the human body.

Powązki 2020

Once again, employees of the Museum of the History of Medicine of the Medical University of Warsaw, together with representatives of the Students Union of our University, visited the graves of professors and doctors associated with the Medical University of Warsaw. During the visit, candles were lit and flowers laid over 30 graves located in two of the most famous Warsaw cemeteries: Old Powązki and Powązki Military.

The yearly event was carried out a week before All Saints’ Day. During its duration, we lit symbolic lamps on the graves, laid flowers – and, if necessary, also cleaned the graves.

Among the graves visited, we could not miss the graves of four outstanding representatives of the world of Warsaw anatomy and pathology: Edward Loth, Witold Sylwanowicz, Ludwik Paszkiewicz and Wiktor Garówka-Dąbrowski, whose graves are presented in the photos below.

The graves of professors and medics distinguished for the Medical University of Warsaw were found thanks to the support of Dr. Adam Tyszkiewicz, director of the Museum of the History of Medicine, who briefly introduced the participants to the profiles of each of the visited figures resting on both necropolises.

Jean-Antoine Houdon, Écorché (Flayed Man), 1767, French Academy in Rome

One of the most famous images of Écorché in modern art. The sculpture was made by the artist at the age of 25 in Rome, as a preparatory study for the marble statue of St. John the Baptist, which was to become a pendant for the sculpture of St. Bruno in the Church of Santa Maria degli Angeli. Houdon attended an anatomy course in Rome, accompanied dissections on human corpses, and diligently studied anatomical drawings in order to accurately depict the sculpture of a man’s physique. The work he created is characterized not only by a very faithful representation of the muscles, but also by an animated pose. The man’s right hand is stretched horizontally in front of him – in a gesture of blessing, which was to be repeated in the figure of St. John the Baptist. Écorché’s weight rests on his left foot, and the right leg is grasped slightly bent with the foot slightly raised, suggesting a step forward that is about to take place. The work was quickly recognized as a separate work of art. Charles Natoire, the director of the French Academy in Rome, acquired it and included it in the collection of plaster casts. Natoire’s successor as director of the Academy, the famous painter Joseph Marie Vien, ordered all students to study this work on a compulsory basis. Houdon himself, realizing that his anatomical sculpture was such a great success, made numerous copies of it in Rome and later in Paris, which enjoyed great popularity in Europe. Especially popular with collectors and art lecturers was the Écorché variant with the hand raised. Houdon’s anatomical works were also copied many times after his death.

Leonardo Da Vinci, The Vitruvian Man, 1490, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice

Drawing by Leonardo da Vinci “The Vitruvian Man” is dated to around 1490. It’s author presented on paper, with a pencil, a naked figure of a man in two superimposed positions with arms and legs apart, and at the same time inscribed in a circle and a square. The drawing refers to the “De Architectura” treatise (datedbetween 30 and 15 BC), created by the famous Roman architect Vitruvius. This ancient work discusses the human body in the context of the search for perfect proportions, which drew the attention of Leonardo, fascinated by human anatomy. Da Vinci believed that the functioning of the human body can be compared to the operation of the microcosm against the backdrop of the universe. On this basis, for example, he juxtaposed the human skeleton with the rocks of the planet, and the action of the lungs during breathing with the ebb and flow of the oceans. The drawing of the Vitruvian Man is stored in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice and is very rarely shown at exhibitions.

Myron, Discobolus, 450 BC, National Roman Museum

One of the most important sculptural works of the classical period in Greek art has survived to our times only in the form of marble copies from Roman times. Myron’s work depicts a naked athlete at the moment of discus throw. His right foot is firmly set in front while his left foot is tiptoe. The torso and head are turned to the right, while the right arm retracts the disc. Thanks to this, the athlete’s pose is very dynamic and the figure is extremely proportional and balanced. The work can boast of a very large knowledge of human anatomy, at a time when human corpses were not yet dissected, and body observations were only possible during sports competitions or battlefields. In Myron’s work, stretched muscles, modeled skin folds, and nails on the athlete’s legs and hands were reproduced with great precision. The entire performance is characterized by a very high level of realism and the severity of the style, which is mainly manifested in the lack of showing the internal emotions of the discus thrower.

Antonio Pollaioulo, Battle of the Nudes, engraving, circa 1460.

Giorgio Vasari, author of “The Lives of the Most Famous Painters” wrote: “[Pollaioulo] dissected many corpses to see the internal structure of the body. He was the first to show muscles according to the shape and layout of the figures. ”. At the beginning of the second half of the 15th century, artists were just beginning to be interested in the structure of the human body, and Antonio Pollaiuolo, a Florentine painter and sculptor, is today considered a precursor of such methodology. Soon after him, other artists began to carry out autopsies, including Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. His most famous engraving entitled “Naked Men Fight” has an eminently classicising style. To this day, the subject of the depicted scene has not been fully explained. The most frequently mentioned hypotheses include references to mythology , stories from the times of ancient Rome, athletic competitions with the participation of gladiators, aimed at celebrating the death of an outstanding individual. The characters presented in the graphics are captured in various poses and angles. As a result, their muscles are tense and exaggerated. Such a presentation, achieved with the help of the so-called the return strokes that can be obtained in pen and ink drawings made it possible to demonstrate the artist’s great knowledge of the anatomy and movement of the human body. The engraving could therefore also serve as a didactic aid for other artists.

Marco d’Agrate, Statue of St. Bartholomew, with his own skin, , 1562, Duomo di Milano

Standing in the transept of the Milan cathedral, the statue of St. Bartholomew is the most famous work of the artist Marco d’Agrate. The apostle is depicted with his skin hanging over his shoulders and around his body, which at first glance looks like a scarf. Such a performance refers to his death as a martyr, extremely cruel, as he was skinned alive and then beheaded. A reference to his Christian faith is the Bible held in his left hand. The masterpiece is characterized by an extremely precise capture of the anatomy of the body and muscle structure. Perhaps the artist was familiar with the famous treatise on the anatomy of Andreas Vesalius, which appeared in Venice in 1553. An interesting fact is the inscription added to the pedestal of the sculpture with the following text: Non mi fece Prassitele, bensì Marco d’Agrate, characterized by the artist’s faith in his own skills comparable to himself a master from ancient times, Praxiteles.

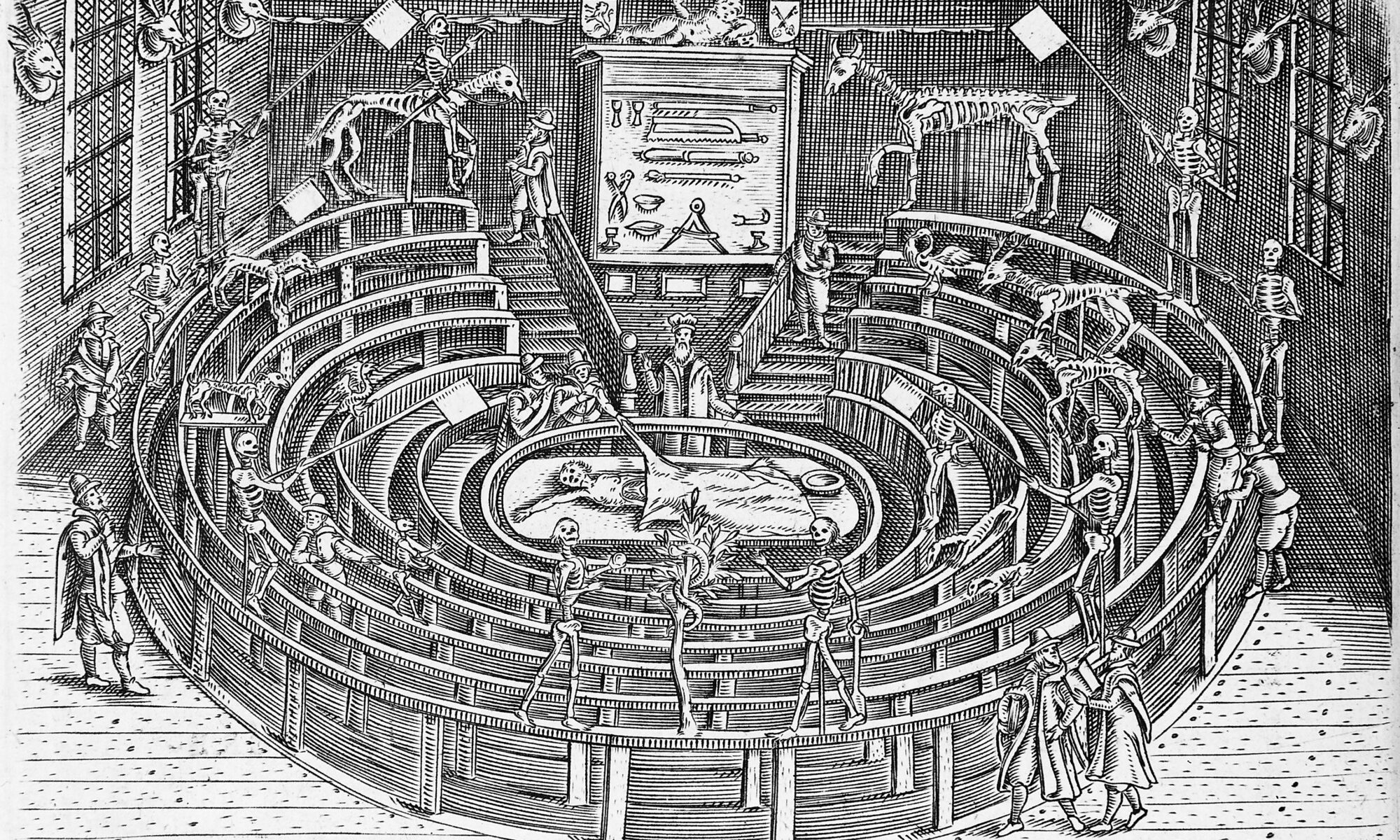

Rembrandt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp, 1562, Mauritshuis museum in The Hague

The painting of Dutch master is the most popular work of modern art, combining the worlds of anatomy and painting. Painted at the request of the Amsterdam Surgeons Guild, it shows the eponymous Dr. Nicholaes Tulp, in the company of seven viewers, carrying out an autopsy of a man (Adriaan Arisza) who was executed on the same day. In the first half of the 17th century, dissections were carried out once a year, usually in winter, and were increasingly often made public. Over time, they were treated as performances comparable to a visit to a theater or an opera, therefore, apart from doctors and students, all interested parties participated in them after paying for inexpensive tickets. From a scientific point of view, the section presented by Rembrandt was not properly done because the autopsies always began with cuts to the stomach and chest. Here we are dealing with the anatomy of the human hand, and more precisely the mechanism of bending the fingers. In the lower right corner of the painting, an open book is visible, which is considered to be the anatomical treatise De Humani Corporis Fabrica, written by Andreas Vesalius. Rembrandt painted one more painting showing the human dissection – “Doctor Deyman’s Anatomy Lesson” which has not survived to present times.

William Pink, Smugglerius, 1834, Royal Academy Schools in London

The collection of the Royal Academy Schools in London includes a plaster cast by William Pink called Smugglerius showing the anatomy of a man captured in a pose referring to the famous Hellenistic sculpture of the Dying Gaul. Pink’s work is a replica of a bronze figure made in 1776 for the anatomist and physician William Hunter by the Italian sculptor Agostino Carlini. Its name was related to the body of a thief sentenced to death by hanging (en. Smuggler), which was skinned after the execution for educational purposes. The bandit who was executed in Tyburn was most likely one of the three criminals: James Langar, Robert Harley, or Edward George. Thus, these criminals accidentally and undoubtedly undeservedly (because of their profession) entered the annals of art history. Giving the Latin name to the sculpture meant that artists in the second half of the 18th century grasped the relationship between nature and art in reference to the desire to present the ideal from ancient times. Carlini’s work, and a later replica of Pink, were copied many times by successive generations of painting students. The most famous drawing showing the anatomical details of Smugglerius’ muscular body was made by William Linnel in 1840.